Dr. Jake Clark

Award-winning Data Scientist

STEM Education and Outreach Evaluator

Planetary Astrophysicist

Fulbright Future Scholar Alumni

Award-winning Data Scientist

STEM Education and Outreach Evaluator

Planetary Astrophysicist

Fulbright Future Scholar Alumni

Thank you for visiting my website. I'm Jake, a Data Scientist, STEM Outreach Evaluator, Science Communicator, and Planet Finder currently based in Canberra, Australia's capital city.

I've dabbled in a bit of everything and have detailed a range of my experiences within the tabs above. From researching the chemical fingerprints of other worlds to interviewing heavy music artists and developing tools for STEM organisations across the country, I'm sure you'll find something of interest. If you'd like to learn more or have a chat, feel free to connect via the email or LinkedIn icons at the end of this page!

I grew up in the bottom 10% of Australia—a proud crow-eater (South Australian) from the character-building northern suburbs of Adelaide (5108 represent). Growing up in such an environment, I had no role models around me who had even finished high school, let alone pursued a university degree. However, my passion for exploring the cosmos broke this social barrier and, well... started from the bottom, now we're here.

With two degrees from the University of Adelaide (Bachelor of Science Honours and Bachelor of Science in Space Science and Astrophysics), I joined the Questacon Science Circus in 2016. I travelled across the country, presenting science shows to regional and remote classrooms across Australia. I traded in the clown shoes (who am I kidding—these US 15s aren't going anywhere) for a bunch of telescopes in regional Queensland, starting my PhD at the University of Southern Queensland in 2017. After completing my PhD in early 2022, I returned to Questacon, where I now utilise my background in Data Science and Science Communication as a Senior Evaluation Officer. I'm working on new and exciting ways to evaluate and measure the effectiveness of Questacon's numerous STEM outreach initiatives and experiences. Learn more on my STEM Evaluation page.

Music, and in particular "heavy" music, has been my vice since early high school. Moshing in a pit is very cathartic for me personally, but I completely understand that it's not for everyone! I've had the absolute privilege at Radio Adelaide to interview some of my biggest idols, including Slayer, Killswitch Engage, Parkway Drive, A Day To Remember, Story of the Year, Enter Shikari, Protest The Hero, and more. If you'd like to know more about the tunes I dig, I've created a Spotify playlist below to show you how similar—or maybe dissimilar—our tastes in music are.

My wardrobe only offers two variants, band shirts and sports jerseys. If I'm not headbanging to some heavy earworms, you'll probably see me barracking for ALL of the sportsballs. Favourite teams include Port Adelaide Power (AFL), South Adelaide (SANFL), St. George Illawarra (NRL), Baltimore Ravens (NFL), Houston Astros (MLB), Toronto Raptors (NBA) and Liverpool (EPL) to name a few.

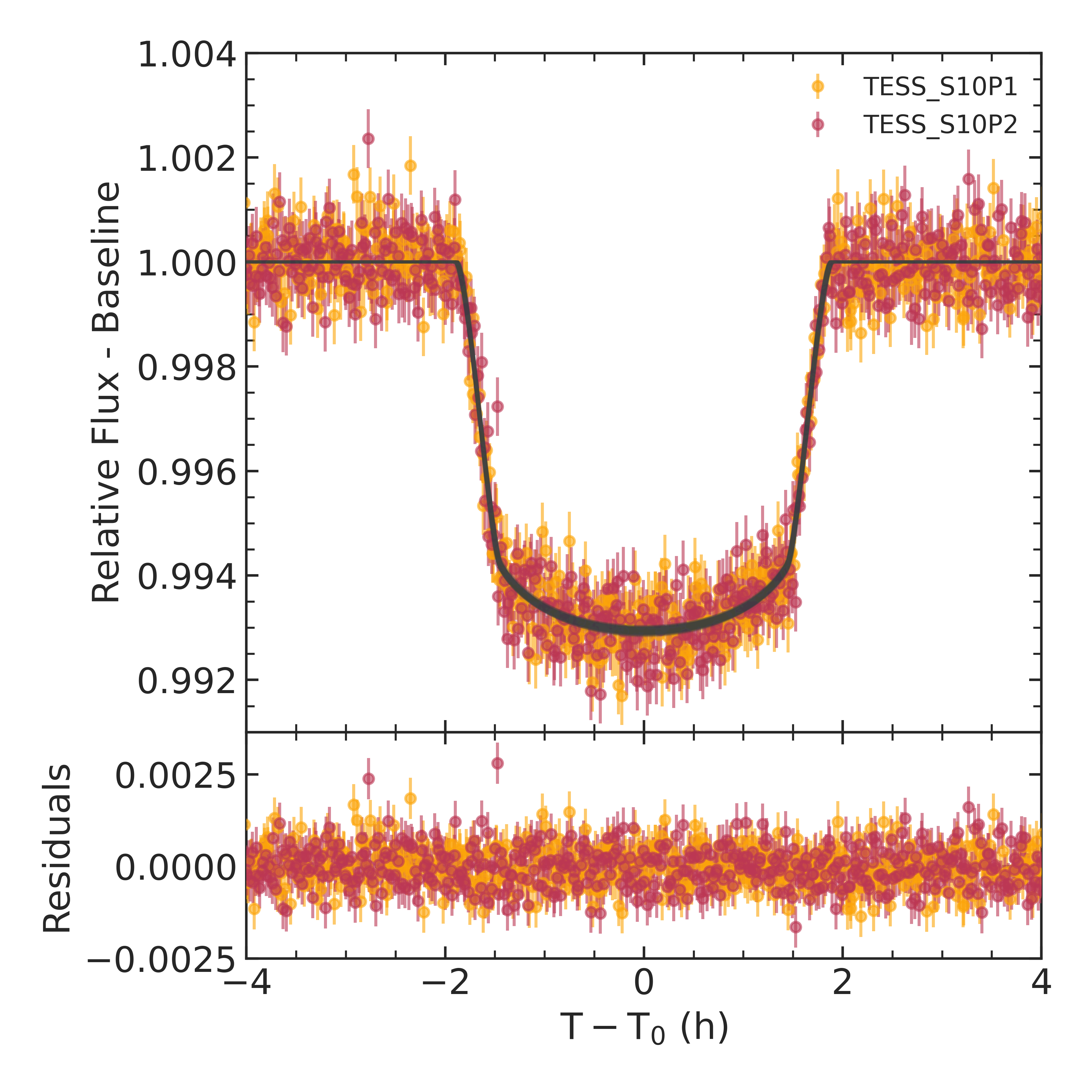

During my PhD, I was fortunate to co-author and lead over 25 research papers in the field of Planetary Astrophysics. All of which you can find and read here. My main area of research was discovering and characterising planets outside our Solar System, known as exoplanets. As of August 2024, astronomers have discovered well over 5,700 exoplanets, with the two main methods for detecting these alien worlds being the Radial Velocity (where the planet's gravity tugs on the star, causing its light to change colour) and Transit Photometry (a periodic dip in the host star's light) methods.

My PhD research, conducted at the University of Southern Queensland, enhanced our understanding of the fundamental properties of exoplanets and their host stars, using Australia’s largest-ever star survey, known as GALAH.

GALAH has observed over 750,000 stars in the Southern Hemisphere to better understand how our galaxy was formed and evolved into its current state. I used the GALAH survey to examine stars observed by NASA’s planet-finding mission TESS and to refine the properties of stars that have, or could potentially have, exoplanets. Why is this important?

Well, the size and mass of an exoplanet depend entirely on its host star. When astronomers and astrophysicists discover a new world, we usually determine the mass and radius of the exoplanet based on the size and mass of its host star. In some cases, the fundamental properties of stars, including their mass and size, can have errors of up to 100%. This means that the size of some stars could be twice as big or tiny as a pin! These errors then translate back to the planet's properties. We need to accurately determine how large and massive these smaller worlds are if we hope to make accurate measurements. My PhD redefined the stellar mass, radius, and age of thousands of stars and also assisted in analysing and refining hundreds of exoplanetary systems discovered by TESS’s predecessor, the K2 mission, to precisely determine the mass and radii of planet-hosting stars with an error margin of 5%!

Not only did I aim to improve the physical characteristics of these stars and planets, but I also wanted to understand what these planets are actually made of. Are they composed of fairy floss? A whole planet made of Vegemite? The Radial Velocity technique, mentioned above, uses precise measurements of a star’s spectrum. This spectrum encodes the chemical abundances of the star, showing the distribution of different materials within it, particularly the amounts of planet-building elements like silicon, iron, magnesium, and other elements found within a planet-hosting star.

We can use these stellar abundances as proxies for the rocky material that their smaller planets might be made of! From this information, we can make better-informed decisions about whether these exoplanets could be terrestrial-like in composition, and thus have a better sense of whether life could exist on these alien worlds. My research revealed that only half of the planets we find will be similar in composition to those in the Solar System... the other half? Unlike anything we can begin to imagine! If you'd like to know more about this, I highly recommend checking out the works of Caroline Dorn, Cayman Unterborn, and Natalie Hinkel.

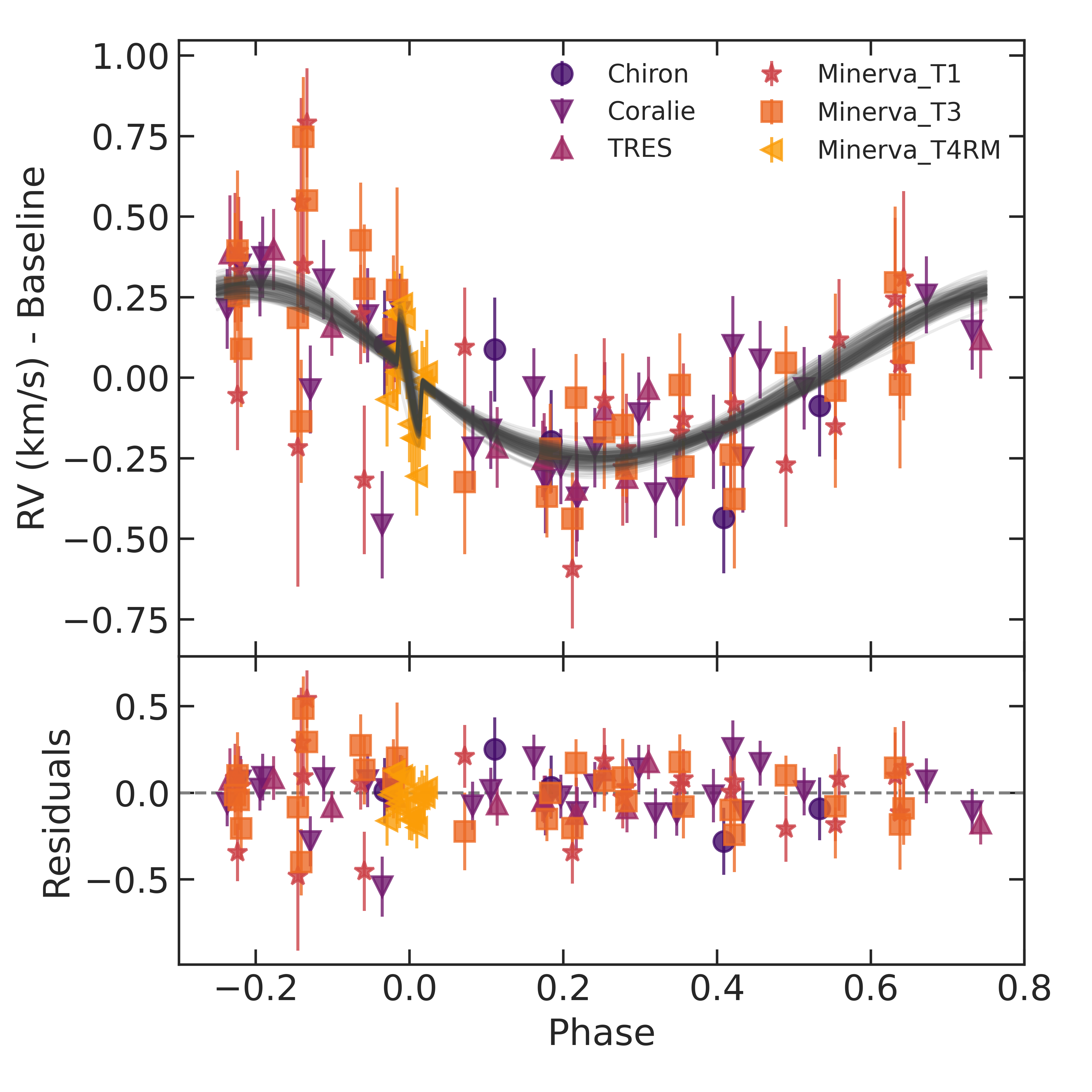

During my PhD, I was incredibly fortunate to assist in the commissioning of MinERVA-Australis, the Southern Hemisphere's only dedicated observatory supporting NASA's new planet-finding mission, TESS. TESS is a space-based observatory that scans the entire night sky for exoplanets. These planets are then confirmed using ground-based observatories like MinERVA-Australis in regional Queensland, Australia. The facility’s five 0.7 m telescopes can either work in unison or independently, allowing us to target faint objects or observe multiple bright stars simultaneously! Since the commissioning phase, I’ve been one of the key observers for the project, helping to discover four exoplanets so far! In addition, I use the observatory to obtain high-precision chemical abundances of host stars, which helps determine what their planets could potentially be made of.

If you’d like to learn more and want something to put you to sleep, you can access my PhD Thesis. If you cannot access any of the research above, please contact me, and I’d be happy to share it with you!

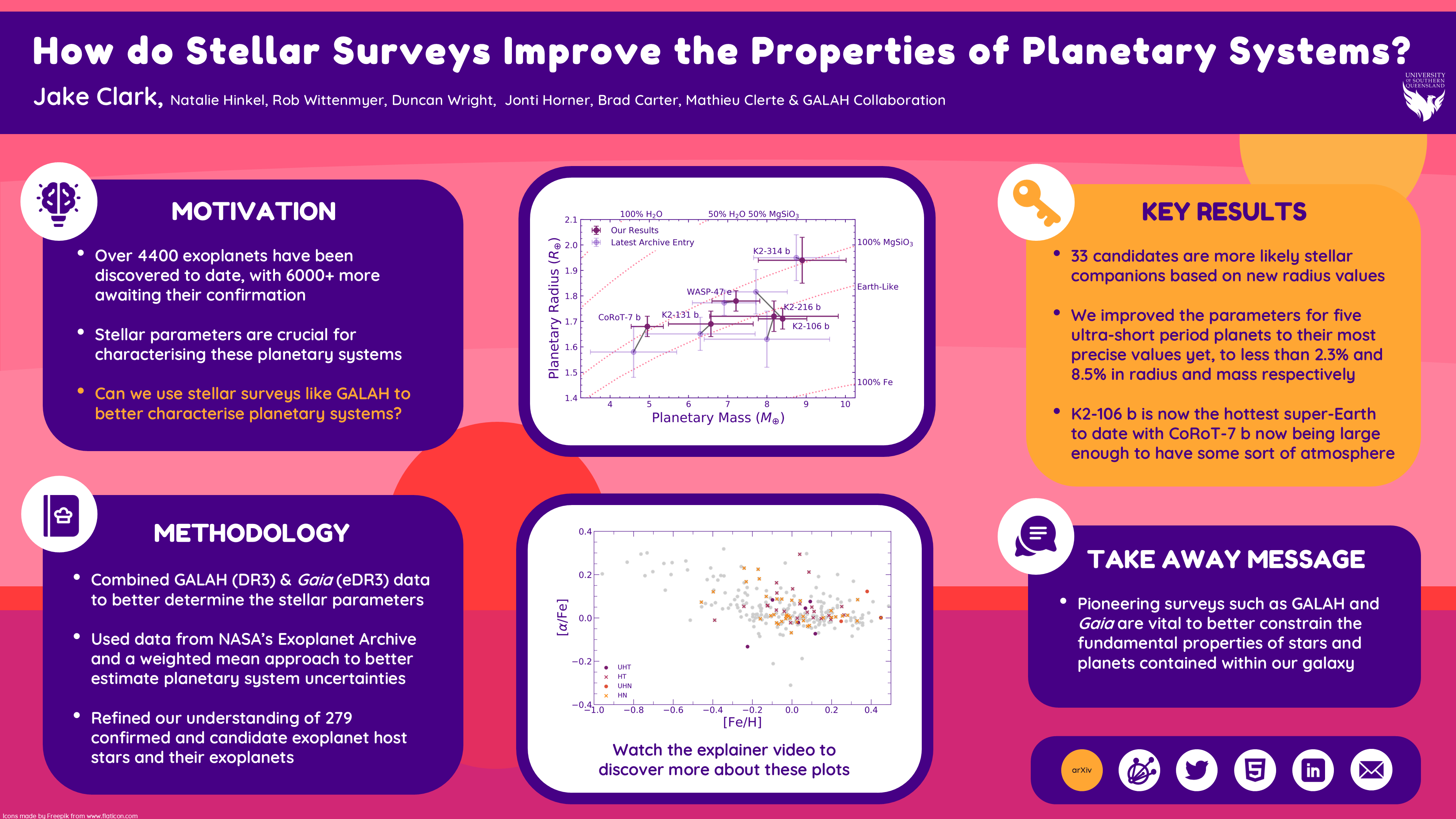

Below are some conference posters I created for several conferences during my PhD. You can access the PowerPoint slides for inspiration here.

Below are my professional and academic CVs. If you need further clarity on anything, please get in touch

If you haven't realised by now, I. LOVE. SPACE!! And I love talking about it as much as I do researching it. Previously, I was the Student Representative for the Astronomical Society of Australia's Education and Public Outreach Chapter and way back in 2016, I received the opportunity of a lifetime, running away and joining the circus... the Questacon Science Circus.

The Science Circus is a practical Master's degree in Science Communication Outreach, run jointly by Questacon, the National Science and Technology Centre, and the Australian National University. I travelled all around Australia, presenting engaging STEM shows to primary and high school students. This experience definitely honed my science communication skills, which are invaluable for any modern-day scientist!

Throughout 2019, I was the lead PI for an Advanced Queensland Engaging Science grant, where I travelled across regional South East Queensland, getting junior primary students to dance through the solar system and build their very own alien worlds from dough. In the coming months, I'll have my Build-A-Planet activities up on the astronomy education resource website astroEDU. My main outreach activities during my PhD revolved around the University of Southern Queensland's Astronomy for Schools and Communities program. It's an incursion-based program where astronomers travel around to different schools around regional Queensland, showing off UniSQ's immaculate dark, regional skies with portable and easily accessible telescopes. In mid-2019, The Conversation ran its first Curious Kids night at UniSQ, where I got to talk to a room full of budding scientists about bags of poo on the Moon and oceans of liquid "farts" on Uranus... it was LOADS of fun!

Some of my other outreach escapades including presenting my science at numerous events across Australia including Pint of Science, Gold Coast Skeptics Club annual Darwin Day, Science in the Pub Tasmania and up to Outback Queensland for the Queensland Government's Flying Scientists program to name a few.

In my previous life, I founded and coordinated the heavy music radio show MOSH at Radio Adelaide, Australia's oldest community radio station. Combining this experience with my Science Circus training, I've become pretty media savvy, yarning on the radio, TV, print and social media about the latest astronomical research across the globe. Below are some of my media highlights and is by no means an exhaustive list.

I've had the absolute pleasure of writing for The Conversation, a NGO that aims to bridge the gap between researchers and the boarder community. All of their articles are written by academics and researchers, and are published under a Creative Commons license. That means if you are a publisher/blogger etc. reading this and like these stories or others, feel free to republish them at your own discretion!

Yeah look, it's a bit weird being on the other end of the mic. But I enjoy it nevertheless, as you can see me with UniSQ's self-proclaimed "Media Tart with a Heart" Prof. Jonti Horner below at the ABC's Southern Queensland studio!

And here I was thinking I had a face for radio! Apparently not. I've had the absolute pleasure in being a part of two commercial TV science shows, Scope and Brain Buzz. I've appeared on Scope twice, once was showcasing how we can use 3D scanning and printing technology to print a copy of TV host. The other time was showing off MINERVA-Australis and how we find exoplanets in regional Queensland. In 2018, I managed to snare the lead role for Brain Buzz's live show held at both the Brisbane Town Hall and Toowoomba's flower festival. The Brisbane Town Hall show alone was to 1400 people

So here’s the low down. You’ve just sat down at your desk on a Monday morning. The smell of coffee permeates through the room as you slowly scroll through the hundreds of emails you’ve received during the weekend. But one single notification stands out… TESS has just dropped some hot off-the-press candidates. Some are located in the Southern sky, your favourite hemisphere! But, you want to know more about the physical and chemical characteristics of these candidate host’s... where do you begin to look? Well, we’ve got you fam!

I’m going to try and summarise the last four years of my life in one interactive poster… so strap yourself in. If you're viewing the PDF of this interactive poster, I highly recommend checking out the website version of it instead (https://jake-clark.github.io/#TESS21).

Involving fewer shovels and more optical fibres, galactic archeology is a growing sub-field in astronomy, aiming to better understand the formation and evolution of our home galaxy, the Milky Way. Galactic archeology surveys are huge stellar surveys, with rich data sets containing both the physical and chemical properties of stars contained within our galaxy (and sometimes even beyond).

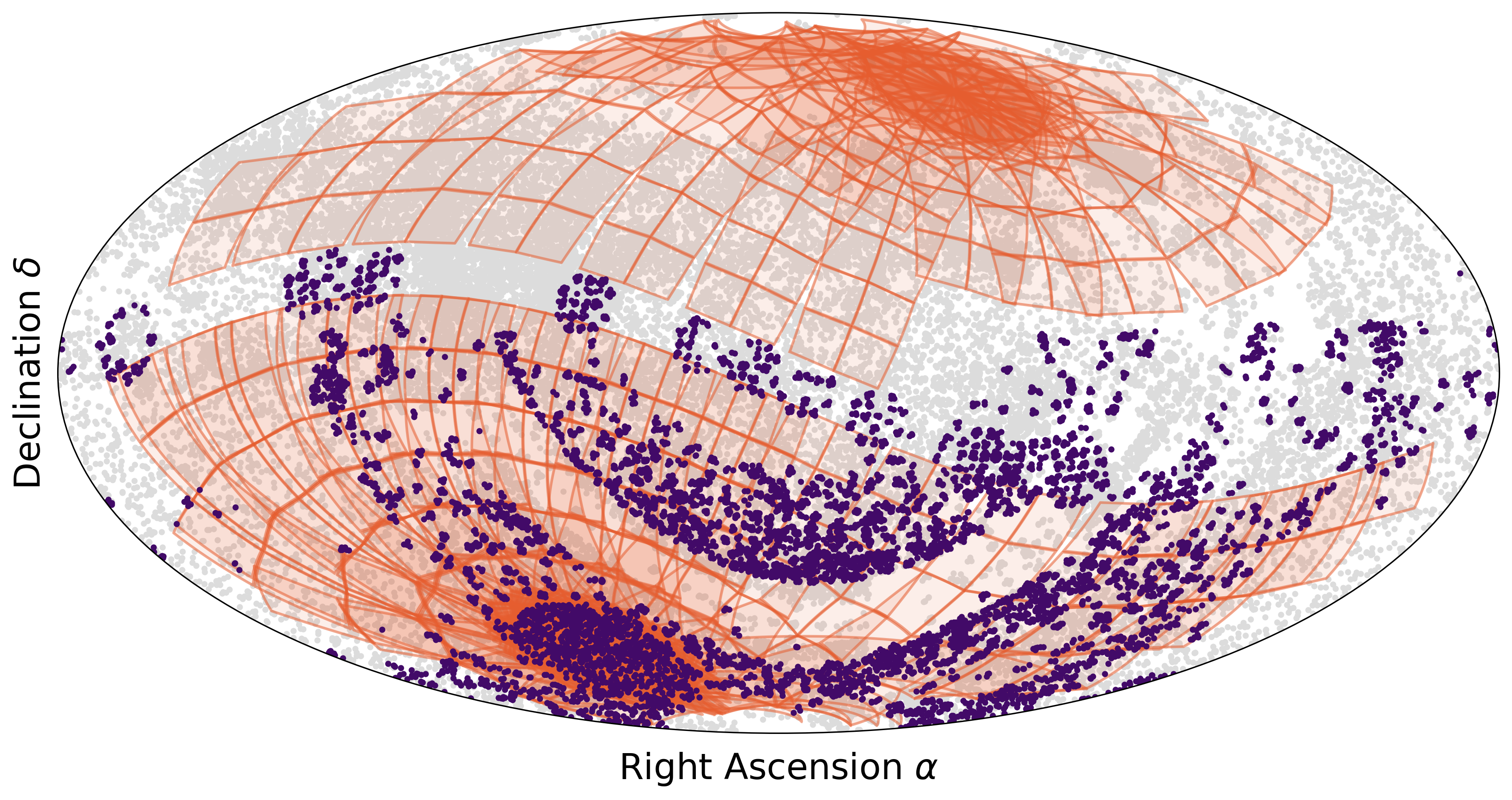

As you can see with the plot below, the overlap between the TESS sectors, in orange, and stars observed with Australia’s Galactic Archeology with HERMES survey (GALAH), in purple, is incredible. So why not utilise these big surveys to further characterise current and future TESS planetary systems with GALAH? Sounds like a no brainer to me!

Now that is a cool question to try to answer. The answer to this question can be found below. But the TL;DR is: Around half of the rocky worlds found by TESS will likely have geological compositions unlike any object found within our Solar System!!

You’re probably thinking, Jake and team, how did you work that one out?! Well, here goes the recipe list, without the doom scrolling of me verbosely describing how I made the cosmic cake before the actual cake recipe.

Ingredients:

Recipe:

And voila, you've just created the GALAH-TESS catalouge! If you'd like to get your hands on some freshly squeezed science, both the data and paper are now publicly available!

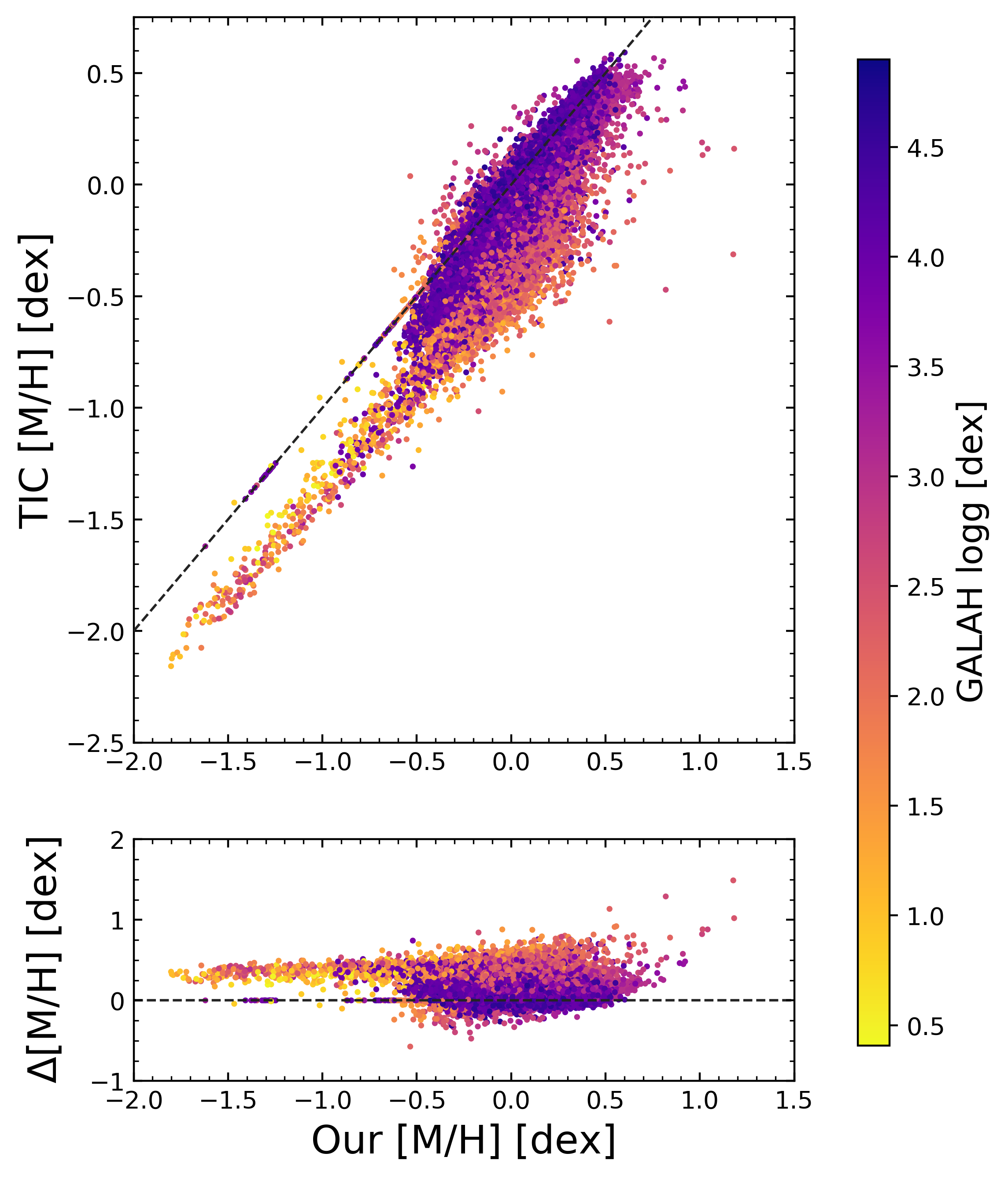

Real talk for a second though. As a member of the astronomical community, I know that we love making our lives simple. Some simplifications include; always searching for log-log relationships, assuming PETA doesn’t know about our obsession with spherical cows in a vacuum and more importantly, assuming the periodic table only contains hydrogen, helium and “metals”.

This assumption really breaks down for our iron-poor and alpha-rich thicc disk friends (which you can’t tell if the star is a thin or thick boi just based upon their iron-abundance alone) and can have disastrous effects on your isochrone results. We’ve all been there, lessons learnt! Just remember [Fe/H] != [M/H].

One of the coolest realisations during my PhD is knowing the sheer diversity of stellar interior, photospheric and isochrone models that are out there and available to planetary astrophysicists and astronomers like ourselves. These various models can change the calculated physical properties of the stars being derived, depending upon what models you choose.

As you’re probably well aware, we don’t directly measure the mass or radius of the planets we discover. We calculate a planet’s mass and radius through the relative relationships between a star and planets’ mass and radius. Thus if the stellar properties change, then so do the planet’s.

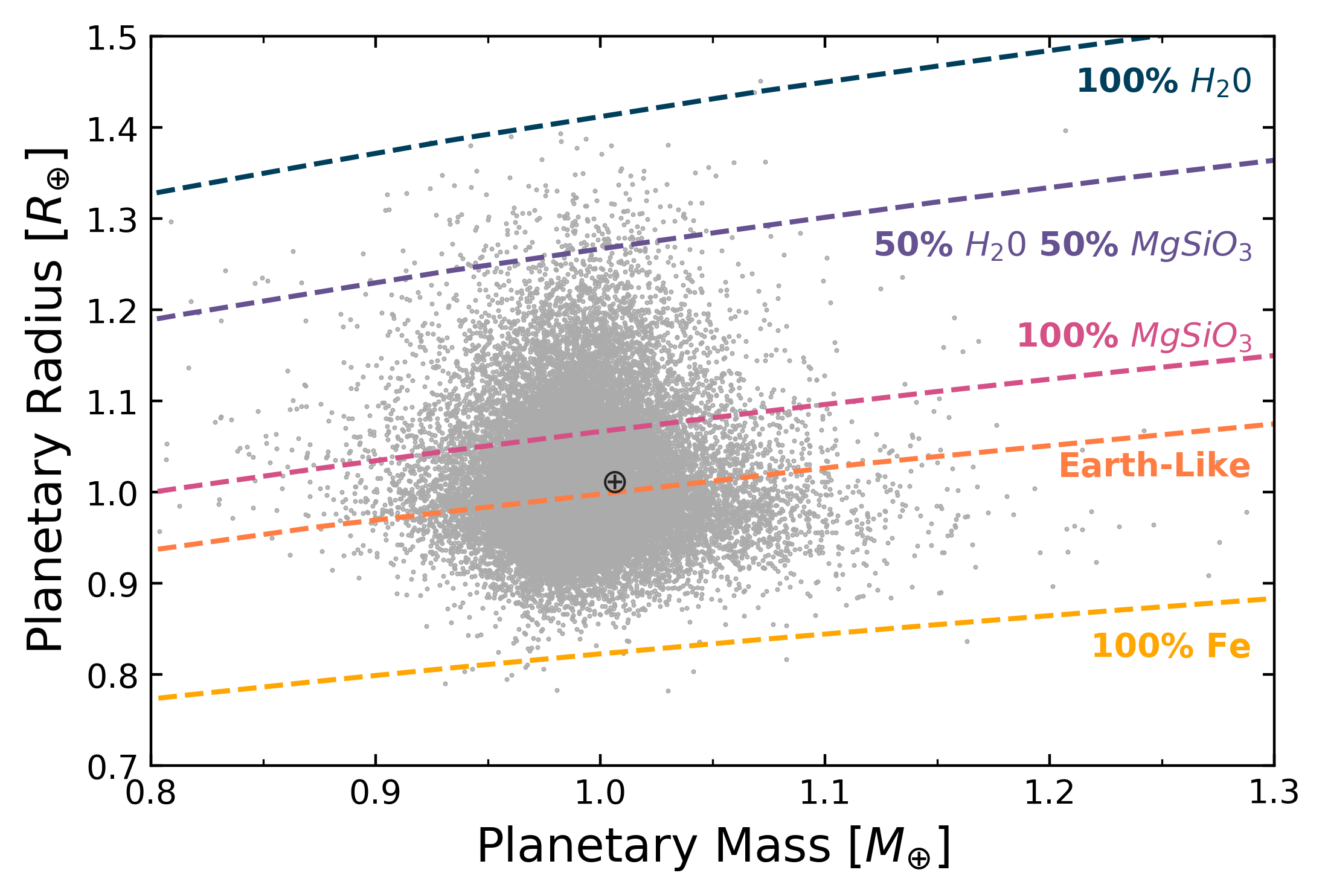

So I wanted to test something, a kinda cool experiment as it were. What if you discovered THE first Earth-massed and Earth-sized exoplanet. You’ve used the GALAH-TESS catalogue because you know how awesome and comprehensive it is to determine the mass and radius of this planet. BUT, what if you used the stellar parameters from the TIC instead. How different would your “Earth-like” world be?

As you can see from the graph above, your “Earth-like” world would now be a various mix of different compositions. Some of these would have extremely questionable compositions required for life as we know it. I’m not saying that one method of deriving stellar parameters is better or worse than the other in this comparison. I’m just trying to show that consistent stellar parameters from various sources matter when you’re trying to determine the characteristics of exoplanetary systems.

Australia’s GALAH survey is an absolute treasure trove of stellar data, boasting not only the physical properties of the stars being observed, but the chemical abundances for over 20 elements as well. Stellar abundances are incredibly important to help us exoplaneteers determine the likely chemical and geological compositions of rocky planets these stars might host.

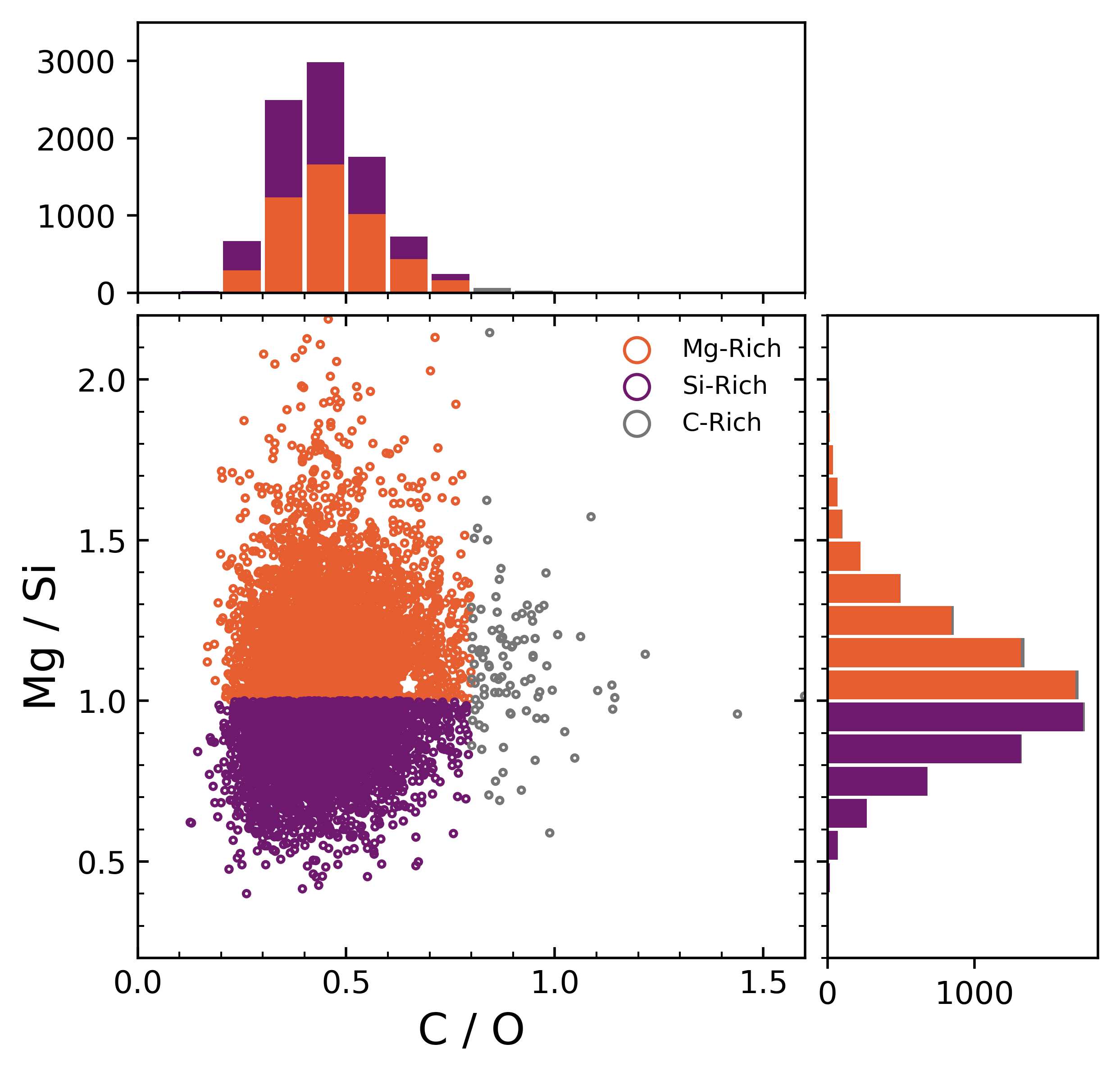

If you want to build a planet, some of the key raw ingredients include Iron (Fe), Magnesium (Mg), Silicon (Si), Carbon (C), Oxygen (O). People a lot smarter than me have been able to determine the likely composition of exoplanets by looking at their host’s Mg/Si and C/O molar ratios (also known as abundance ratios, linear ratios … another story for another day).

So what do you need to know? Well there are three key regimes that’ll help determine the likely composition of rocky worlds from their host stars, them being:

So if you were to find a potential rocky world orbiting around a TESS star, what would its likely composition be? Well, eager beaver, before you scroll further, take the poll so I can see what your answer might be before you see what we found out in the plot below! Wanna know the answer? Of course you do! Drum scroll please 🥁🥁🥁

As you can see in the plot above, just over half of the stars within the GALAH-TESS catalogue will likely host planets akin to those found within the Solar system. Less than half of these stars will likely host either Silicon or Carbon-rich worlds, completely alien to bodies that we are used to orbiting Sol. So why should you care? Well, if we want to find a planet just like our own, we need to also consider its geological and chemical composition to constrain its habitability. One can do that right now thanks to the abundances found within the GALH-TESS catalogue!

With nearly half of planets discovered by TESS either being Silicon or Carbon rich worlds, this may motivate and grow the great field of exogeology to further study the potential habitability of such exoplanets! The discoveries and research of which is entirely exciting, just on its own.

There are slight caveats to equating the abundances of planet-building elements within a star to that of its planetary companions, and is still an exciting field of research (see the work done by Adibekyan+ 21, Plotnykov & Valencia 20 and Wang+ 18).

As we’re all aware, 2020 was an absolute dumpster fire. BUT, there were some redeeming moments through it all, including GALAH’s announcement of their third data release, GALAH DR3. What is so freaking cool about GALAH DR3 compared to DR2, is the inclusion of the TESS-HERMES and K2-HERMES surveys within DR3. Aptly titled, these surveys include stars located within the K2 fields and TESS’s Southern Continuous Viewing Zone, allowing for more planet-host and candidate-host stars within GALAH DR3… ooo the juicy science that can come out of a data set like that!

With a similar recipe to that of the GALAH-TESS catalogue above, we combined data from GALAH DR3, Gaia EDR3 and 2MASS to recharacterise 280 confirmed and candidate exoplanet hosting stars.

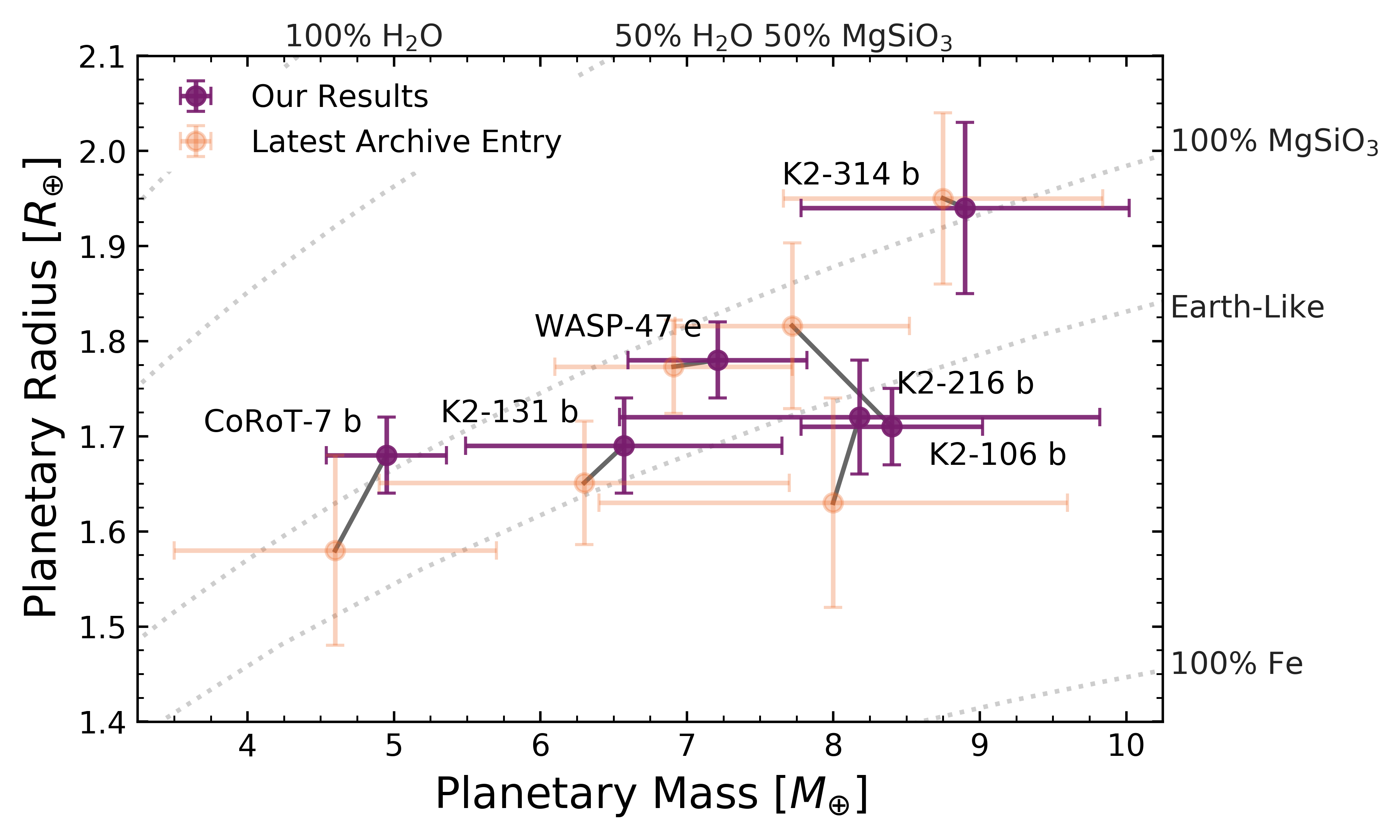

What’s even better, is now NASA’s Exoplanet Archive boasts numerous records for the same system, instead of just one record per system. We’ve used the new Archive and a weighted mean approach for observed properties (i.e transit fluxes, radial velocity amplitudes etc.) to recharacterise over 400 confirmed and candidate exoplanets. This weighted mean approach means that we’re able to better estimate the planetary system uncertainties, which can then lead to us getting a better idea of what the planet’s composition might be!

So what have we learnt? Well, we’ve found out that 33 candidates are more likely stellar companions based on new radius values. We are also able to improve the parameters for five ultra-short period exoplanets, in particular, refining the mass and radius of WASP-47 e, K2-106 b and CoRoT-7 b to their most precise values yet, to less than 2.3% and 8.5% respectively!!

With combining GALAH DR3 and the NASA Exoplanet archive we have a new gold medal holder for the “hottest super-Earth” with K2-106 b now having an equilibrium temperature of 2570 K, far exceeding the condensation temperature of most refractory elements. But wait, there’s more!

Our radius estimate for CoRoT-7 b suggests that the exoplanet is large enough for an atmosphere to contribute to its overall radius. What type of atmosphere could a rocky planet hold at 2027 K? Well, that question is well above my pay grade, and I’ll leave it up to the community to work that one out!

What's great about GALAH's data releases is again the combination of physical and chemical properties for over 600,000 stars. We were inspired by Dai 21+ who showed that Ultra-Hot Neptunes might favour iron-rich stars compared to their smaller rockier counterparts, suggesting Ultra-Hot Neptunes and Ultra-Hot Jupiters might form through similar mechanisms.

We have shown independently that there might be some truth to this, as the spread of Ultra-Hot Neptunes tends to iron-rich stars, compared to Ultra-Hot Terrestrial worlds. However, we have also added another dimension to this, a star’s alpha abundance, which can be used as a proxy for thick disc stars ( ~ [alpha/Fe] > 1.0 for thick disk stars) and also a proxy for age (Older stars tend to be iron-poor and alpha-rich. For more details check out Sharma +20).

The ⭐⭐INTERACTIVE⭐⭐ plot below shows from our work, that there are very few thick disc stars that host hot terrestrial and hot Neptune worlds. There are also no ultra-hot terrestrial or Neptune exoplanets orbiting thick disc stars within our sample. We are still working out as to why that might be the case. But, if you have an inkling, please get in touch and I would be more than happy to collaborate!

This interactive plot from our research suggest that ultra-hot Neptunes tend to favour iron-rich stars compared to their terrestrial counterparts. We also see a lack of ultra-short and short period planets around thick disc stars, suggesting different planet formation mechanisms for different stellar populations.

That title might seem a bit obvious, but in the context of this poster, let’s talk about stellar rotation. Ground-based follow-up of TESS targets generally rely on radial velocity measurements to not only confirm the exoplanetary nature of candidates, but also be able to calculate fun stuff like mass, density, composition etc. However, stellar rotation plays incredible havok on obtaining nice, crisp lines for high precision radial velocity follow up. Basically, the faster the star rotates, the harder it will be to confirm planets with smaller radial velocity signals.

We can then plot the stellar rotation of planet-hosts along with confirmed planets with already calculated mass measurements… but what’s the point of that, huh? That’s a nice baseline to have, but I have used the Chen-Kipping mass-radius relationship to forecast the potential masses of both candidates and confirmed planets within GALAH that have no mass measurements, to obtain a predicted mass. From that mass, one can calculate a predicted semi-amplitude for the mass signal (orange) and plot that against known planets that have confirmed mass measurements, both in GALAH (purple) and those within the NASA Exoplanet Archive (grey).

Click and drag the plot around. See where your favourite exoplanet sits on this plot and see if there are any candidate or confirmed planets without mass measurements around your favourite one.

For the likes of TOI-1219.01, a mass confirmation will be extremely tough, with a host’s stellar rotational velocity of 58 kms-1 and an expected RV semi-amplitude of just 2 ms-1. This plot thus can help the SG2 and SG4 community better prioritise what targets they should and shouldn’t be allocating resources too.

There are quite a number of exoplanets that have an expected RV amplitude between 1-10 ms-1 with their stellar host’s rotational velocity between 10-4 kms-1. We expect that for the stars nearer to 4-5 kms-1, this might be more of an upper limit due to the resolution of GALAH, so these targets might actually have slower rotating hosts, which might make them reasonable targets for high-precision radial velocity followup!

Higher stellar rotation might make following up targets around this cosmic spinning tops tough, but it’s not impossible. Over the last couple of years the Minerva-Australis team, along with teams around the world, have been following up a hot-Jupiter, orbiting around the rapid rotator TOI-778. TOI-778 has a rotational velocity of 28 kms-1, making it a pretty hard star to confirm targets around. However, over the coming months, on an arXiv near you, you will see a paper confirming the planetary nature of TOI-778 b.

The confirmation of this planet has also been part of an exciting Research Experiences for Undergraduates summer program Indigenous Skywatchers with undergraduates at the St. Cloud University. I can not wait to share our results with this awesome community.

You’ve made it to the end 🥳🥳

It’s been a delightful four years, and I hope I’ve shown you how pioneering stellar surveys such as GALAH and Gaia are vital for our community. These surveys help to better constrain the fundamental properties of stars and planets contained within our galaxy and provide a rich data set for planetary demographics, ground-based follow up, recharacterising planetary systems and more. Please feel free to catch up with me during the conference, and if you have any exciting projects that you think I would be perfect to collaborate on, please get in touch. 🖤🤘

Adibekyan, Vardan, et al. "The Chemical link between stars and their rocky planets." arXiv preprint arXiv:2102.12444 (2021).

Brown, Anthony GA, et al. "Gaia Early Data Release 3-Summary of the contents and survey properties." Astronomy & Astrophysics 649 (2021): A1.

Brown, A. G. A., et al. "Gaia Data Release 2-Summary of the contents and survey properties." Astronomy & astrophysics 616 (2018): A1.

Buder, Sven, et al. "The GALAH+ survey: Third data release." Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 506.1 (2021): 150-201

Buder, Sven, et al. "The GALAH Survey: second data release." Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 478.4 (2018): 4513-4552.

Chen, Jingjing, and David Kipping. "Probabilistic forecasting of the masses and radii of other worlds." The Astrophysical Journal 834.1 (2016): 17.

Clark, Jake T., et al. "The GALAH Survey: using galactic archaeology to refine our knowledge of TESS target stars." Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 504.4 (2021): 4968-4989.

Dai, Fei, et al. "TKS X: Confirmation of TOI-1444b and a Comparative Analysis of the Ultra-short-period Planets with Hot Neptunes." arXiv preprint arXiv:2105.08844 (2021).

Morton, Timothy D. "isochrones: Stellar model grid package." Astrophysics Source Code Library (2015): ascl-1503.

Plotnykov, Mykhaylo, and Diana Valencia. "Chemical fingerprints of formation in rocky super-Earths’ data." Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 499.1 (2020): 932-947.

Sharma, Sanjib, Michael R. Hayden, and Joss Bland-Hawthorn. "Chemical Enrichment and Radial Migration in the Galactic Disk--the origin of the [$\alpha/\rm Fe] $ Double Sequence." arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.03646 (2020).

Sharma, Sanjib, et al. "The TESS–HERMES survey data release 1: high-resolution spectroscopy of the TESS southern continuous viewing zone." Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 473.2 (2018): 2004-2019.

Skrutskie, M. F., et al. "The two micron all sky survey (2MASS)." The Astronomical Journal 131.2 (2006): 1163. Stassun, Keivan G., et al. "The revised TESS input catalog and candidate target list." The Astronomical Journal 158.4 (2019): 138.

Taylor, Mark B. "TOPCAT & STIL: Starlink table/VOTable processing software." Astronomical data analysis software and systems XIV. Vol. 347. 2005.

Wang, Haiyang S., et al. "Enhanced constraints on the interior composition and structure of terrestrial exoplanets." Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 482.2 (2019): 2222-2233.

Wittenmyer, Robert A., et al. "K2-HERMES II. Planet-candidate properties from K2 Campaigns 1-13." Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 496.1 (2020): 851-863.